Approaching Indian Cinema

This has been a much more confounding start to the year than I had anticipated. I thought, sure, Indian films are obviously different than American, French, or Japanese, but, hey, I get it! I’ve watched a lot of international films! I couldn’t absorb every cultural nuance in Japanese or French films, but I got by! Themes are universal! Plots are dissectable!

I was wrong.

Indian cinema is as complex as its incredibly diverse history and is as varied as the number of languages spoken there. Mark Cousins put it better in his 15 hour documentary opus, The Story of Film, when he said, “The story of Indian film is as vast as the country”. He was not exaggerating. To understand Indian cinema has taken me months of watching movies, reading reviews by Indian members of Letterboxd to help contextualize what I’ve just seen, and buying a few books to help flesh out the history of India before its independence in 1947.

In my past few years of deep diving into the cultural waters of France and Japan I’ve never had to beef up too much on history because the social and cultural norms remained the same (though both countries cinema’s reacted deeply to the effects of World War 2, they started from a place of deep cultural understanding of the collective “self”, meaning that while the subject matter may change, they cultural eye through which films were made largely remains the same despite historical shifts). But both of those countries had been independent for most of their existence. For that matter, so had India, one of the world’s most prolific melting pots throughout history. Unlike Japan or France, India was newly emerging from British rule.

How you decide when the terms of British rule began may differ, but its effect is important to the history of film in the country. British influence absolutely began as early as 1600 with the formation of the East India Trading Company. It expanded in 1638 when the first British factories were built in Madras. Many say the victory of Robert Clive in Bengal in 1757 is the formal date when British rule began. More conservative, or Empire friendly folks, may point to 1858, when the British formally took control and named the first British Raj. But that date, while neat in its definition of one nation taking control of another is mute; as Britain had essentially destroyed India’s middle classes by taking virtually all manufacturing in the country to support its empire. That had begun happening before 1858. The British excluded Indian goods from export as they built up their own factories in India; turning the middle class into an ungodly populous rural, agrarian class with no way to support itself. By 1834 - 24 years before the first Raj - Lord Bentinck, a British officer wrote, “the misery hardly finds a parallel in the history of commerce. The bones of the cotton weavers are bleaching the plains of India” (Chakravarty: 27). The Economic Times puts the estimate of the dead due to British policy during their rule between 60-165 million people. History is the trail of breadcrumbs to understanding culture. So while this timeline may seem like a digression, understanding the effects of British rule partially informs where India was by their independence in 1947.

With that date in mind, my movie year has started around 1947.

I’m not speaking from a place of personal knowledge when I say that independence is messy. It’s an easy thing to say from where I sit. That known truth is more felt the more you watch Indian films***. India inherited a rigid caste system that was sown onto their diverse identity by the British. That caste system is on display in virtually every film and very much still exists in India today. The population was still deeply poor and largely agrarian-based by the time of independence. Famine was ongoing in parts of the country. Yes, India was a “new” country in 1947, but it was not unburdened by its past. The cinema of India reflects all of this. Indian pictures helped give India an identity to the rest of the world, but it also allowed India to search for itself through its pictures. The cultural aspirational self feels meshed together; like Play-Doh colors smooshed together, with their immense historical greatness and very diverse population, creating a collage effect that I’m uncertain the writers, filmmakers, and studios completely understood how to manage. By the time of independence, Indian cinema was truly taking shape, though films are still trying to marry history, aspirations, and reckoning with class and caste.

Access to Indian Cinema

So with that lengthy preamble to set the table for my first post about Indian cinema, I think we can now talk about movies. Or can we? Let’s talk about film access for a minute.

Again, framing this based on the past two years of deep dives into international cinema, it’s glaringly obvious that if you want to watch movies in a meaningful manner, you must invest in physical media. Beyond that, you really have to invest in a region-free DVD player as you’ll have to buy DVDs from across the globe. Understandably not every Japanese, French, or Indian film has been distributed in North America. I would guess that less than 3% of their annual output is ever available here through streaming or retail. So spending the time to find them in crucial.

In this year, more than any others, I expected some additional work. Indian cinema is well-known around the world; though 9 out of 10 people probably believe Bollywood is Indian cinema, rather than a regionality associated with Hindi language films. But I don’t know anyone who knows anything about Indian cinema beyond Satyajit Ray. And getting even more granular, I don’t know anyone who had watched any of his films outside the Apu Trilogy. I imagined it would be a year of ordering DVDs from overseas. I wasn’t prepared for how hard it would actually be.

There’s a phrase that has stuck in my mind for the past few months when I think about Indian cinema. “Racism by omission” is a quote, again, from Mark Cousins in The Story of Film, and though he wasn’t talking about Indian cinema, it absolutely applies to it. For the most prolific national cinema in the world to be virtually unwatched and unavailable in America very much has the stench of racism attached to it. Not only are Hindi, Urdu, Bengali, Malayalam, and Kannada films impossible to find streaming, they’re also incredibly difficult to find on DVD (blu ray isn’t even an option here). Most of the films from the 40s through the 70s (where I currently am in my viewing) were maybe - maybe - released on DVD once in the 90s or early 2000s. So finding any way to view 100 Indian movies has been a slog. Here in the U.S. there’s Eros Now, a streaming service you can add-on to your Prime or Apple TV account for $4 a month, but it’s not easy to navigate, has no way to filter your search, and the selection is still incredibly limited. Amazon has some of the bigger Hindi/Bollywood movies; especially starting in the 60s. For anything before the 1960s, I’ve relied heavily on crummy Youtube transfers with less-than-perfect subtitles (something I haven’t dealt with too much since the early 2000s when I would order Hong Kong kung fu pictures regularly from Vietnam or Cambodia). The visuals of these earlier films are also degraded; the picture and sound decayed from decades of no care. So, if you want to look into watching some Indian films, I strongly suggest you simply keep tabs on my public list on Letterboxd of A Year in (Indian) Movies to know which ones are definitely available somewhere, somehow.

The Movies

As of writing this, I’ver watched 37 Indian films. Of those, about half are Hindi. 9 are films by Satyajit Ray (Bengali). That brief statistical chit chat illuminates the difficulty of finding films outside the hallowed halls of Criterion or the large output of Bollywood. But what’s available is what’s available, so here is a brief rundown of the films so far contextualized (very loosely) by the decade of their release.

The 1940s

Most of the films I found to watch from this decade are historical epics. Films that gaze back to moments of historical significance when Indian traditions won the day, or when they didn’t, the films recontextualize the defeat as a moral victory, such as in Sikandar (1941), which dramatizes the partial conquering of India by Alexander the Great. Humayun (1945), directed by the popular director Mehboob Khan, was another highlight of the historical epic before independence that marries the historical epic with contemporary tastes for melodrama.

The other films from the 1940s that I’ve seen are deeply indebted to early Hollywood melodramas as much as Parsi Theatre; which is where the use of song as emotional insight for characters originates. Films like Anmol Ghadi (1945) and Andaz (1949) take, arguably, some of the worst lessons from American melodramas and blows them out into wildly unrealistic visions. But - they were hits. And they very much are stylistically in line with the Parsi traditions of “realism and fantasy, music and dialogue, narrative and spectacle…all combined within the framework of melodrama” (Dissanayake, 20). If Parsi theatre sounds like a lot, that’s because it was designed to reach as broad an audience as possible using every trick to keep audiences’ attention. The Hindi films of the ‘40s absolutely travel the same path. Most of the films are close to 3 hours in length, rich in songs, extended takes that last beyond the actionable thrust of the scene, and include plots within plots that don’t add anything to the overall narrative, but contrive to keep you in your seat longer.

Out of this generation of films, a few stars emerged that I followed well into the 1950s. Nargis, the female lead in Andaz and other melodramas like Barsaat (1949) is an incredibly gifted actress who manages in every film to be sympathetic, independent of her characters age or personality. She was almost always cast as a sympathetic woman who is usually the victim of societal norms of the day (a “woman’s place”), religious norms, or the rigid caste system; which is constantly reinforced in the movies as an insurmountable wall. The caste system is almost always present, especially in the contemporarily set films of the day and while it makes for an easy melodramatic device to keep lovers separated, etc. it is never challenged.

Raj Kapoor (who also directed Barsaat) also emerged and became the global face of Indian films in the 1950s. While he wasn’t known in the west, he was arguably the most famous actor/director throughout Asia and Russia in the 1950s because of his dead-on Charlie Chaplin comedic sensibility, which breathes air into otherwise claustrophobic storylines of the time.

The 1950s

In broad strokes, this decade belongs to several filmmakers and their films, which altered the trajectory of Indian films.

Raj Kapoor continued his assent to worldwide acclaim with Awaara (1951) and Shree 420 (1955). Awaara is a serious melodrama - again partnered with Nargis Dutt - that bolstered Kapoor’s popularity, but it’s Shree 420 that turned him into a comedy star. He plays a poor country man who comes to the city, where he’s almost instantly robbed. He’s then taken in by a woman whom he falls in love with, but he lets his ambition outway his affections. It’s an effective melodrama that’s obscured by Raj Kapoor’s insistence of doing a Charlie Chaplin impression; complete with hat and mustache.

Guru Dutt started to make his own films like Aar Paar (1954), Pyaasa (1957), and Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959) that made him a household name as both an actor and director. While Raj Kapoor was definitely more popular, Guru Dutt was making much more interesting films and is a more accomplished director.

Pyaasa operates as a large cultural commentary on art, the creator, and fame. It focuses on Guru Dutt as a poet who is unpublished and poor until people think he’s died. His poetry then becomes the most important art of his generation. It’s a beautiful story well told, but even here, as he challenges assumptions of artistic integrity and public acceptance, the film reinforces societal norms and the caste system throughout. Kaagaz Ke Phool is arguably his masterpiece, which borrows heavily in both visuals and themes from Citizen Kane, but it doesn’t take away from the films’ impact. Though it apparently ended his directing career before the decade was even over.

Nargis made the film that’s consider “the Indian Gone with the Wind”, Mother India (1957), a nationalistic film that, more than any other film of the decade, is a tale of the women’s burden, her place in society as both servant and savior, and reinforces the caste system so completely that she kills her own son to protect the perception of herself, her family, and her village. The film includes numerous songs of struggle and pain; including one where the agrarian village all join together to form a human outline of India as they sing in the fields they plow.

That may seem like preamble though. The decade firmly belongs to Satyajiy Ray. He released 4 films in the 1950s and they are all masterpieces. Pather Panchali (1955), the first film he made and the first of the Apu trilogy was labeled “absurd to compare to other Indian cinema” in The Times of India upon its release; making it known generally that new cinema was being born in the country. Before filming began, Satyajit Ray and his cinematographer, Subrata Mitra, had never filmed anything in their lives. They would go on to complete the trilogy by the end of the decade, winning the Golden Lion along the way.

During the decade, Ray also released another singular masterpiece, The Music Room, proving that he wouldn’t be contained to one kind of film for his career.

Ray’s films stood directly opposed to some of the other films of the decade. Films like Mother India and the bulk of other films project the importance of India over all other concerns; even family. Ray filmed his characters in the Apu trilogy with such empathy and emotion to prove that struggles within the family system were often all-consuming to the point where the state is an abstraction.

The 1960s

The ‘60s expanded upon the melodrama template of the previous decades. Movies like The Cloud-Capped Star by Ritwik Ghatak (every bit a contemporary of Satyajit Ray), Woh Kaun Thi, Jewel Thief, and Padosan expanded melodrama and began to incorporate more popular genres of the time like thrillers, ghost stories, broad comedies, and who-dun-its. This openness and expansion of the boilerplate melodrama was aware of shifting interests within the Indian population and took freely from Hollywood tropes to build on, once again.

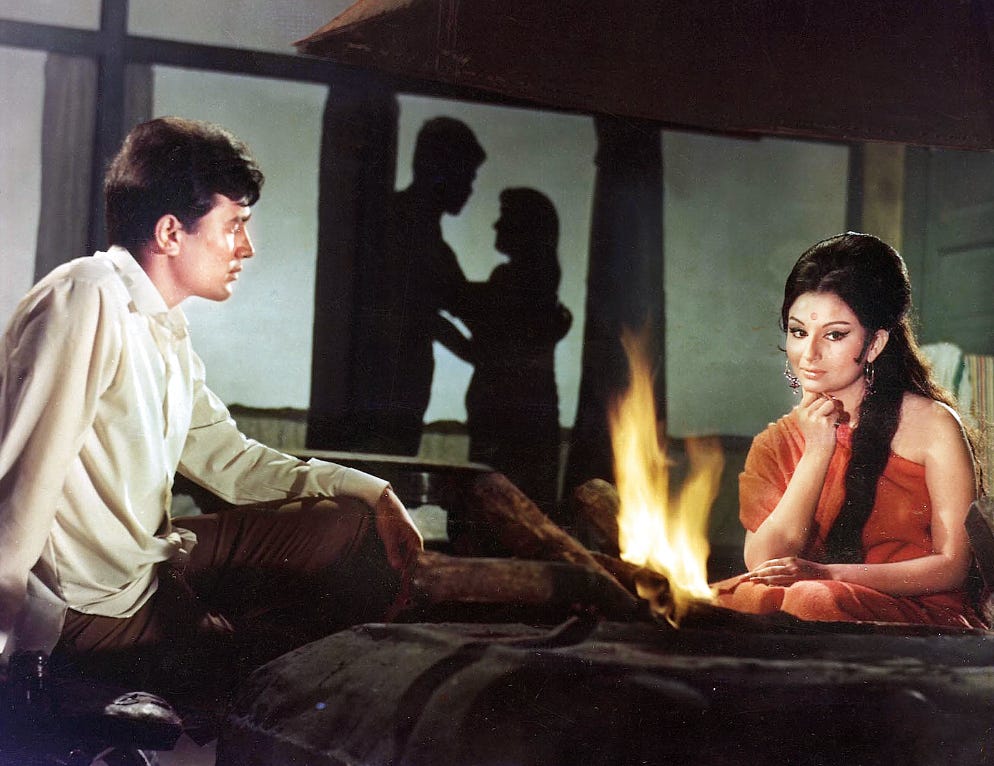

The Bollywood film didn’t completely disappear though. Excellent entries like Aradhana are over-the-top melodramas (this one involves a pregnancy out of wedlock, a plane crash, a jail stint for an innocent person, hidden identities, etc) that are less stuffy and consuming with the drama and let both actors and scenes breathe a bit more. The claustrophobia of tight shots and studio sets are traded in for open vistas.

Outside of Bollywood, Satyajit Ray continued to gain credibility internationally for Indian cinema with classics like Devi (the first film for the incredibly gifted actress, Sharmila Tagore, who was only 14 when she made it), Charulata, The Big City, and The Hero; all considered classics of Indian cinema.

That’s all for this week! If you’d like to see every movie I’ve watched from all the regions of India, you can find it here on Letterboxd.

I hope you get to check out some of the films listed here. Many of them are worth your time and effort to find them. Even if they aren’t all 5 star films, seeing how Hollywood melodramas are adapted and changed by these directors and studios is fascinating.

***A note here to say that it’s also hard to even frame these movies as “Indian” films. Gayatri Chakrovorty Spivak said, “‘India’ is a bit like saying Europe…”Indian-ness” is not a thing that exists” (Chakravarty, 19). That becomes more and more clear as I watch more movies in Urdu, Malayalam, Kannada, etc. India has 22 official languages, so painting them with one brush is an absurd notion, but for the sake of ease of reading, I will continue using the term “Indian” as a kind of geographical shorthand.